Ask an evolutionary psychologist to explain the evolutionary psychology way of thinking to you. I am fairly confident they will give you the following example. Humans evolved in environments where sugary, energy dense foods were scarce. Thus, they evolved a strong motivation to consume these foods when available, and, importantly, no ‘stop’ mechanism; they never needed one, there was never enough sugar available for it to be too much. In ancestral environments, this worked fine, but in modern environments where sugary, energy-dense foods are abundant, it causes problems. People over-eat sweet sugary foods, and this is one of the driving factors in the epidemic of obesity.

This is a great example of key evolutionary psychology concepts: the environment of evolutionary adaptedness, evolved psychological mechanisms, mismatch. It’s memorable and everybody seems to be able to relate to it. There is only one tiny problem with it. I almost feel churlish bringing it up. The problem is that everything about could be untrue.

Embedded in this hardy ev psych perennial are a number of propositions, which we can enumerate as follows:

- Sweet energy dense foods were rare in ancestrally relevant environments.

- Humans lack psychological mechanisms whose function is to curtail or inhibit consumption of sweet energy-dense foods when these are abundant.

- (Therefore) as sweet, energy dense foods become more available with modernity, humans consume more and more of them.

- This overconsumption of sugar is a major cause of the obesity epidemic.

My report card on those claims (based, I must stress, on pretty superficial acquaintance with the evidence) is roughly as follows. 1. No; 2. No; 3. Not really; and 4. Probably not.

First claim 1: sweet foods were rare in ancestrally relevant environments. These kinds of things are hard to be sure about, of course, and the food environments humans have successfully lived in are highly variable. But something we can do is investigate the diets of contemporary warm-climate hunter-gatherers. They are not ancestral human societies, but their ecological conditions are closer to that than those of most contemporary populations.

Honey is the sweetest, most energy dense food known. As Frank Marlowe and colleagues show in an important review, warm-climate hunter-gatherers eat loads of honey. In their sample, 15 of 16 warm-climate hunter-gatherer populations took honey, and the other one lived largely on boats. For the Mbuti of the Congo basin, up to 80% of their calories can be from honey at times during the rainy season. For the Hadza of Tanzania, about 30% of what men bring back to camp is honey, and honey accounts for about 15% of all calories consumed overall. The biggest haul of honey brought back to camp in a single day was 14kg. Fourteen kilos! Assuming 20-30 people in a camp, that’s around half a kilo of honey each. Can you imagine what it would be like to eat half a kilo of honey at a sitting? Using the NHS guidelines of 30g of dietary sugars per day, and taking honey as basically pure sugar, that is half a year’s worth of sugar for every person, turning up in front of you, on a single day.

Looking at data like these, it is hard to conclude that in ancestral environments there was never enough sweet food around to select for mechanisms for regulating one’s intake (think about the immediate glycaemic load as much as anything else). A metabolically challenging surfeit of sweet foods was perhaps, in many environments, a regular occurrence. And all our cousins the African great apes take honey too, so, as Marlowe et al. conclude, exposure to honey is a feature that goes back to our last common ancestor with chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas. Before we even talk about fruit.

What about proposition 2, humans have no psychological mechanisms for saying ‘no more!’ to sweet things. Reports of the non-existence of these mechanisms do seem to have been somewhat exaggerated. In fact, French-Canadian physiologist Michel Cabanac has had rather a distinguished career studying them, since well before the ev psych meme got round. It’s a shame nobody thought to check. The sweet-food stop mechanism actually looks like a great example of an evolved psychological mechanism.

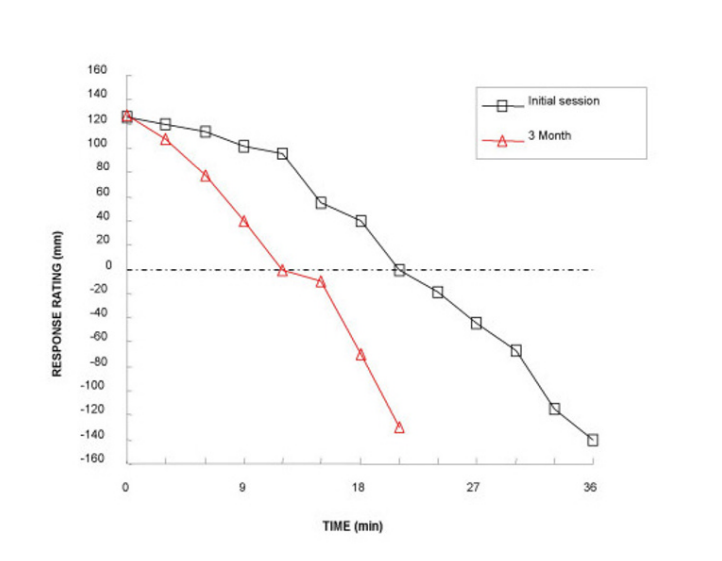

The key phenomenon is ‘negative alliesthesia’, the change in the hedonic value of a stimulus the more of it you have. The term applies to all kinds of stimuli, but it was coined in a 1973 article in the journal Phyiology & Behavior with the stop-too-much mechanism for sweet foods specifically in mind. A more recent study shows the phenomenon very nicely. Participants chewed on a caramel or drank a sweet drink every 3 minutes, for as long as they liked. Each time, they rated the pleasantness of the sweet taste along a line with the centre at ‘neither pleasant nor unpleasant’.

Representative data are shown for one subject below (we can ignore the difference between the initial session and the three month follow up for present purposes). Sweet stuff is pleasant, at first, and progressively less so. Somewhere between 15 and 27 minutes in, it goes from being pleasant to being unpleasant. Within about 40 minutes, it becomes so awful that you have to stop. You simply can’t hack any more. So much for no stop signal, then. These people stopped eating after what is equivalent to a few tens of grams of honey.

My favourite study of negative alliesthesia for sweet foods comes from North Africa, and Cabanac was once again involved. In a population that valorizes adiposity, young women are sequestered away for several months and deliberately overfed in preparation for marriage. In particular, they are overfed sweet things. In the study of young women exposed to this overfeeding institution, only about a third of them gained weight, despite very strong social pressure to do so. The striking finding of the study was a very large decrease in the perceived pleasantness of sweet foods. This occurred in every single subject. The main (presumably unintended) consequence of this institution, it turns out, is not to make people fat, but to make people go off sweet things.

Alright, you say, but everyone knows that proposition 3 is true, no? That people are tucking in to more and more sweet stuff as modernity goes along. Well, that is not very clear either. Annette Wittekind and Janette Walton reviewed the longitudinal evidence on sugar consumption in high-income countries. Thirteen countries had comparable data at more than one time point over the last fifty years, though exactly when the first and last time point was varied (the first was some time after about 1970, the last was some time prior to now). Countries were not easily comparable to one another due to differences in measurement, but the direction of their trend over time could at least be established.

The authors identified 49 possible comparisons, where a comparison consisted of the change over time of a particular age group of a particular sex in a particular country. Most of these comparisons (55%) showed declines or stability in sugar consumption, with 14% showing an increase, and the rest showing something like an increase followed by a decrease. What is clear from these data is that there has been no general increase in sugar consumption in affluent countries in the last few decades; if anything, decreases are more common. Yet, people’s disposable incomes have generally increased over this period. They had more and more money to spend on food (and sweet foods probably got cheaper in real terms). You would think, if they had an evolved craving for sweet stuff and no stop mechanism, that they would have consumed more and more of it. Yet, if anything, the opposite happened. The same pattern you see longitudinally is mirrored cross-sectionally: those who have more to spend on food consume less sugar, not more (because sugars are cheap forms of calories in our food system).

What about proposition 4? The causes of the obesity epidemic are complex. Increased sugar consumption cannot be a monofactorial explanation, not least because obesity has exploded over exactly the time scale that Wittekind and Walton showed sugar intakes to be mostly declining or stable. It’s not even clear that increased overall energy intake is an important cause of the obesity epidemic: though this increased in the late twentieth century (in the USA), some studies now show it falling, even as obesity continues to rise. (A limitation of all these studies is that the energy intake is the theoretical, calorimetric energy value of the foods; this might be very different from the energy that becomes metabolically available.) Just as it is possible for animals to gain fat mass without eating more , the prevalence of obesity may be able to increase in populations without changes in total energy intake being a particularly important driver. It’s not just how much potential energy comes in through the mouth, but what it is made up of, how it is digested, how much energy is expended in movement and at rest, and how available energy is allocated between adipose tissue and other functions such as immunity and cellular repair.

Evolutionary psychologists’ obsession with the uncanny visceral appeal of sweet foods is probably better analysed through the lens of Pierre Bourdieu than that of Charles Darwin. Being slim and eschewing sugar are markers of social class, of distinction, in our present cultural environment. If you are ever in the UK, go to an academic’s house and ask for three sugars in your tea, and you will see what I mean. It is all too easy for the middle-class academics to project their neurotic concern about distinction (do I eat too much sugar and not enough spinach? Is it a failing that I don’t read Heidegger in the original German?) back on to some primeval imagined community. If evolutionary psychology is to make convincing mismatch arguments, they need to have a close relationship to actual evidence, in particular from anthropology and human biology. Otherwise, the present risks ending up explaining the past, rather than the other way around.