Two things we know of are really bad for your health: poverty, and loneliness, aka social isolation. These two predictors come out of epidemiological study after epidemiological study, outcome variable after outcome variable. Other than not smoking, the two main things you can do to improve your health are to have plenty of money and a good social support network. Poverty and social isolation are the two giants of population ill health in affluent societies.

A new paper by Arran Davis, Emma Cohen and myself in Public Health gives a take on how the two giants interact. Arran – who, inter alia, knows more than most co-authors about the ludic chucking of the spear (figure 1) – used data from the European Social Survey, involving 24,000 people from 20 countries, to look at the predictors of the constellation of pain, fatigue and low mood in adults.

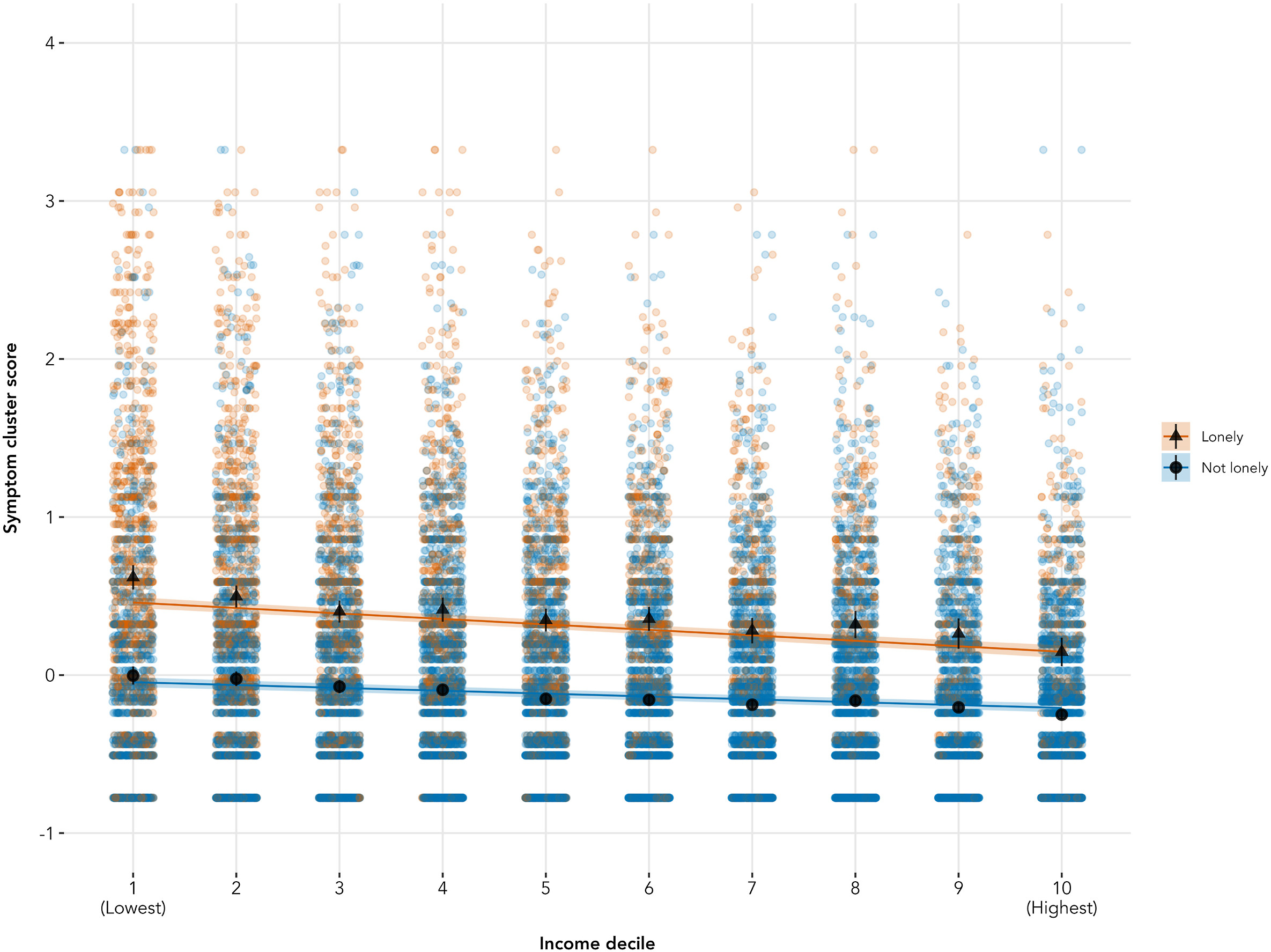

We find that average levels of symptoms increase as you go down the deciles of income, whichever of the 20 countries you are in. But, whichever decile you are in, symptoms are a lot higher for people who report being socially isolated than those who do not (figure 2).

If you look carefully, there is also an interaction between income and social support. Having a low income is not quite so bad if you have social support; or, to put it another way, lacking social support is not quite so bad if you have a high income. Income and social support are both forms of resource, and they are to some extent substitutable. If you don’t have money, your friends and family may be able to help you; and if you don’t have friends and family, you may be able to use money to get the kinds of help you need. You can use either of these resources to avoid or to mitigate pain and fatigue.

This could be a reasonably good-news story. Strong social networks and good social support can to some extent offset the unsalutary effects of low incomes. But, there is a disturbing twist, which is the main theme of this post. Social isolation was strikingly more common amongst people with lower incomes.

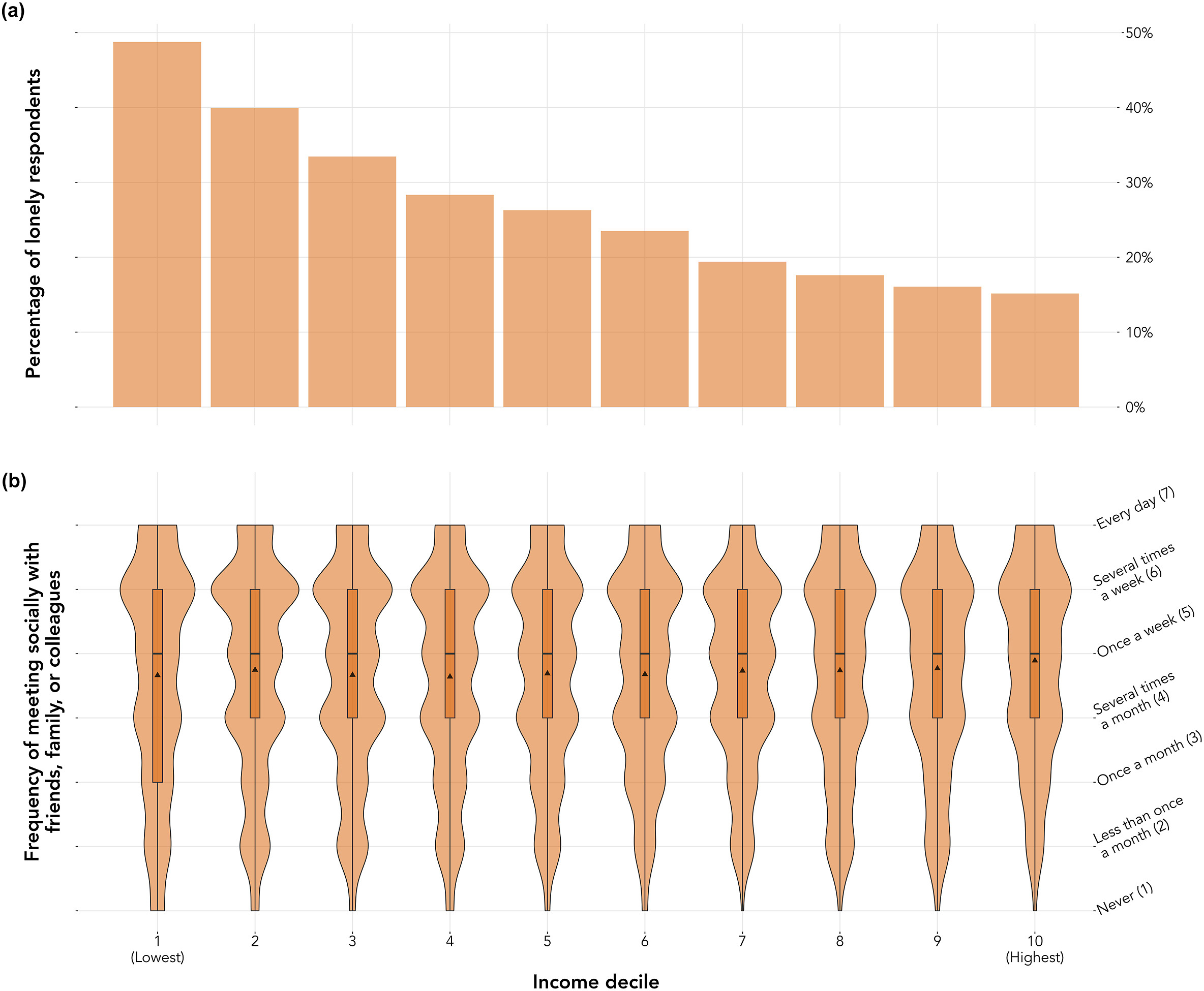

Figure 3 shows, in the top panel, the proportion of respondents reporting that they feel lonely, by decile of income. As you can see, this runs from less than 15% of people in the top income decile to pretty much 50% of people in the lowest. That’s about the steepest social gradient I have ever seen. So, rather than social support being a substitute resource that mitigates the health inequalities arising from income inequality, people with low incomes are hit with a double whammy. Their low incomes make them feel bad; and their low incomes greatly increase their risk of exposure to social isolation, which also makes them feel bad.

The big question is why social support would tend to be so much lower in low-income social networks. The strange thing is that the dataset includes a measure of how often people see their families and friends, and that measure was distributed identically the income spectrum (figure 3, lower panel). So it is not that people with lower incomes are any less likely to actually interact with their friends and family. This mirrors exactly what I observed on a much smaller scale in my work in Newcastle Upon Tyne. People in low-income communities interacted with people from beyond their households just as much as those in high-income communities (if anything, more); and yet they rated their social support much less adequate.

Why would this be? You see other people just as much, but yet you feel a shortfall in your social support. What is going on? There are two obvious and non-exclusive mechanisms that could be at play, one to do with the supply of social support, and the other to do with the demand.

On the supply side, people on low incomes tend to have other people on low incomes in their social networks. Of course, those others are under strain too. They may have less to give; their capacity may be stretched to the limit; they may be buffeted in their availability by the challenges they are facing. So, people on low incomes may simply be able to draw less social support from the same number of ties because of constraints and uncertainty in what those ties can provide.

On the demand side, people on low incomes need to draw more resources from their networks than people on high incomes do, exactly because there is less in their bank accounts. To the extent that the feeling of loneliness is the existence of a gulf between the social support you have and the social support you feel you need, it is obvious that if you need more, the same objective amount will feel more inadequate.

In any event, the strong association between social isolation and poverty has implications. When we control for social isolation in estimate the impact of poverty on health — in that classic and problematic epidemiologists’ way of ‘adjusting for all the other known risk factors we can think of’ — we will be underestimating the total effect of poverty on health, because part of that effect may be channelled via social isolation. And we need to understand social isolation not as some endogenous risk factor, but as itself socially, economically and politically determined, and thus a contributor to social inequalities in health.

Discover more from Daniel Nettle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.